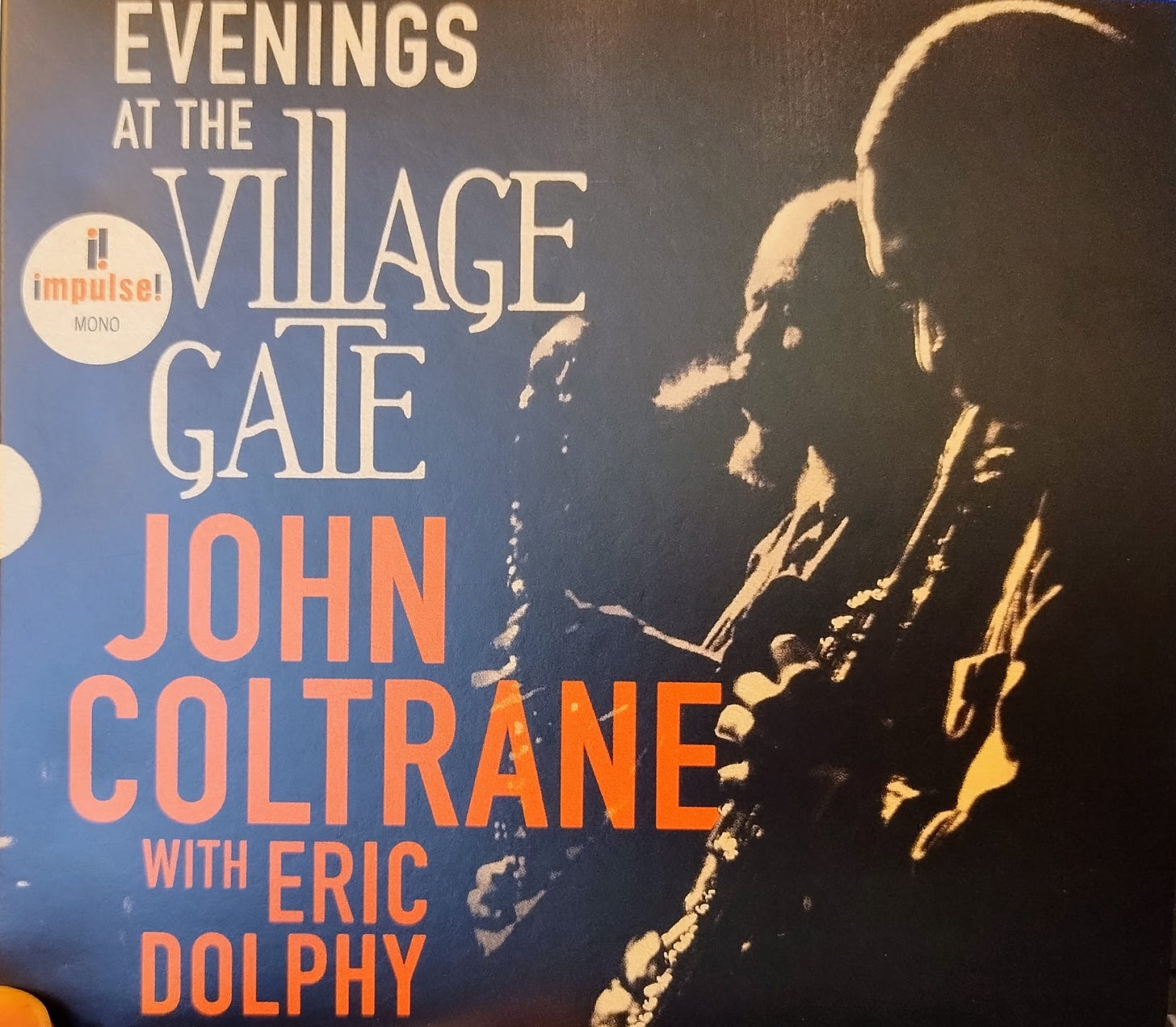

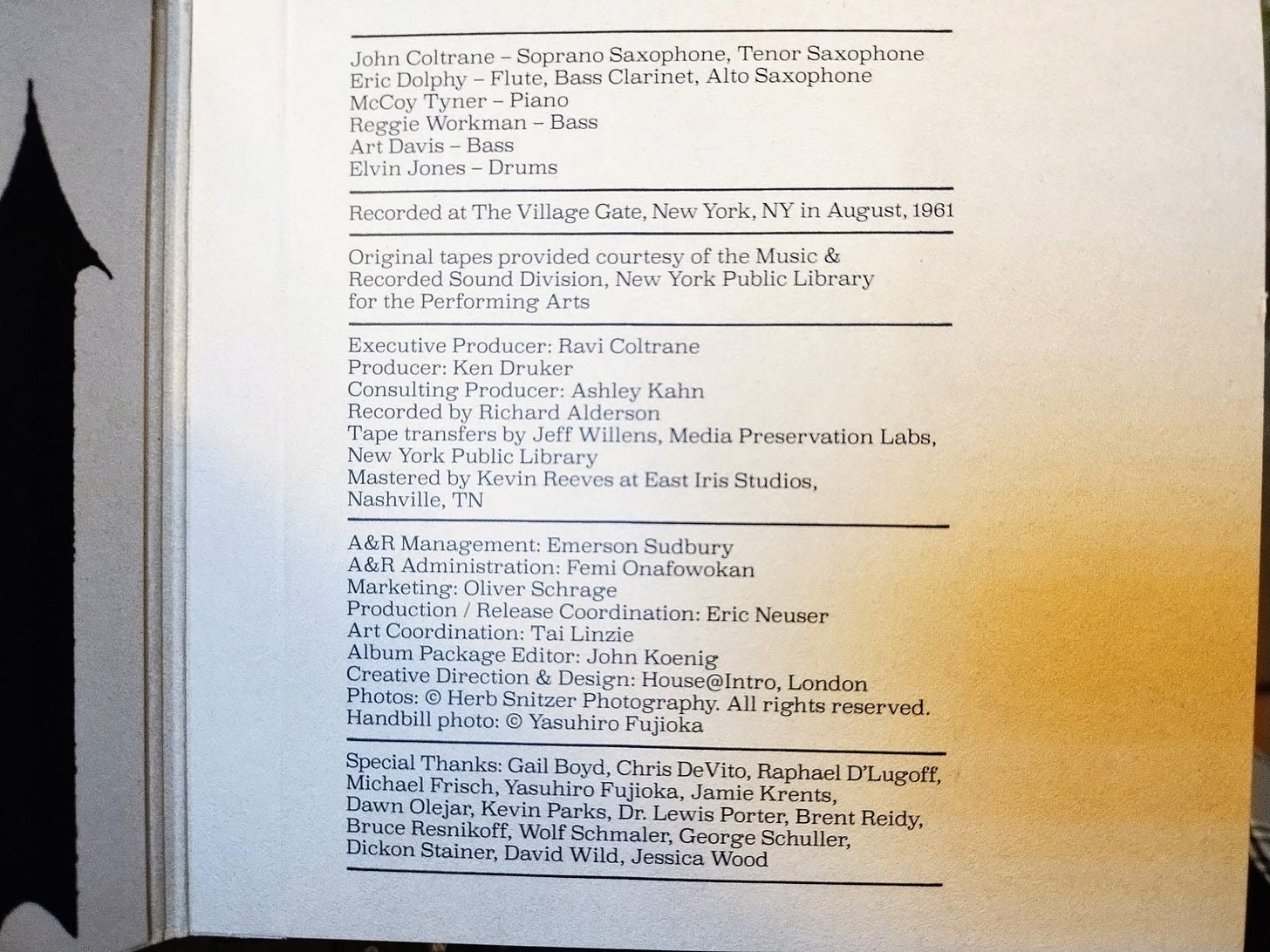

The background of this recording is a testament to how much chance factors into music releases and production. This album would not exist were it not for a bit of casual experimentation and frankly, disregard for the norm of asking an artist’s permission about recording them—at least, from what I have read and heard about this album, Coltrane and Dolphy were unaware they were being recorded. An engineer wanted to test a new microphone, which he hung above the stage. On a night Coltrane and Dolphy were performing, with Elvin Jones on drums, McCoy Tyner on piano, and both Reggie Workman and Art Davis on bass. Coltrane sometimes had two bassists on stage at once, but it seems Workman and Davis worked separate nights.

The album begins after the performance had begun and had gotten into full swing. “My Favorite Things,” from The Sound of Music, which Coltrane recorded in studio, and for which he is probably best known (personal observation), is bopping along already, when the track begins. The recording is good! The most prominent performer on the recording is Elvin Jones on drums. It happens to be one of the cleanest recordings of Jones’s drumming I have heard. All About Jazz’s user poll (AllAboutJazz.com), a couple of years ago, had Elvin Jones as #1 “Legacy Drummer.” He was Coltrane’s classic quartet drummer. Surprisingly to me, he appears on a 1990s album, Kenny Garrett’s African Exchange Student, along with jazz bass legend Ron Carter, who recently celebrated his 86th birthday and is still performing.

Dolphy played flute on “My Favorite Things.” On “When Lights Are Low,” he plays bass clarinet. I was surprised to find how much I enjoy jazz bass clarinet! Anthony Braxton and David Murray were monsters on it. Recently I attended a chamber music performance, and there was clarinet the likes of which I had never heard. Growling through a tenor saxophone is something I read about in Val Wilmer’s 1977 book on late-20th century avant-garde jazz, and the early 20th century piece, which I cannot remember the details of, something like “Prayer for clarinet” by a Russian composer, had the clarinetist growling through the clarinet.

Coltrane improvises at length and with splendor, on “When Lights Are Low,” on soprano sax. Jones keeps a conventional hard-bop swing going. Tyner takes a long solo. Coltrane and Dolphy come in at the end of the solo, playing different melodies, with Dolphy taking the melody and sounding a bit out of tune, and Coltrane keeping his harmonic support part slow and simple.

On “Impressions,” a driving pulse starts at the beginning of the piece, with Jones really bashing the drums. Both Dolphy and Coltrane play from the start, then Coltrane plays an extended, blazing-hot solo on soprano sax. After Coltrane’s solo, which is met with applause, Dolphy solos on bass clarinet. I think Dolphy’s and Coltrane’s styles and choices of instrumentation complement each other, especially on “Impressions.” Dolphy plays in shorter bursts than Coltrane, whose “sheets of sound” involve his seeming never to take the horn mouthpiece out of his mouth. (There’s an anecdote about a frustrated Miles Davis telling Coltrane, during a studio session, to “Take the horn out of your mouth.”)

Throughout the recording, the bass is in the background. It is faint. I try to imagine what a more balanced presentation of the ensemble might sound like. This album is a chance artifact. I take it for what it is, even as I try to imagine what a more deliberate live recording might have resulted in. Jazz drums being one of my favorite instrument choices, the prominence of Jones’s drums, and the overall balance of performers—except for the bassists—satisfies me. There is some liveness even with a single microphone. I hear audience sounds between notes. There is a sense of hubbub, noticeable on track four, “Greensleeves.” Hearing an album such as this one, I think of all the great performances I missed out on and will miss out on. I’m probably missing one at this moment. I am thankful for the ability to commit performances to tape or newer media. I am thankful that I live a life where I have the leisure and peace and quiet, to listen to jazz at home, in my living room. I am thankful for the composers, engineers, producers, performers, their families and friends who support(ed) them, and everyone else without whom recordings such as Evenings at the Village Gate would not appear in my music listening. Thank you all. And to those reading this, happy listening!