Listening: Bill Evans, Trio 64, LP; Bill Evans Trio, Trio ’65, LP

“Everybody digs Bill Evans”; a life cut short, two full-length listening reviews.

Like so many great jazz musicians, pianist Bill Evans died before his time, at 51 years of age, after struggles with drug addiction and disease. He was a heavy smoker as well. He left behind what is widely regarded as some of the best jazz piano ever recorded. His gentle and relatively simple though skillfully improvised way of playing appealed to a wide audience, and his performances in the trio format are classics. Verve has been releasing reissues of classic Verve albums, in a series called Acoustic Sounds, as 180-gram “audiophile,” vinyl LPs. I’m going to give a close listen to two such albums, albums which seem to belong together and not only because their names are similar, Bill Evans’s Trio 64 and Trio ’65. Though not lengthy, I try to comment upon what my impressions of the main aspects of each album are.

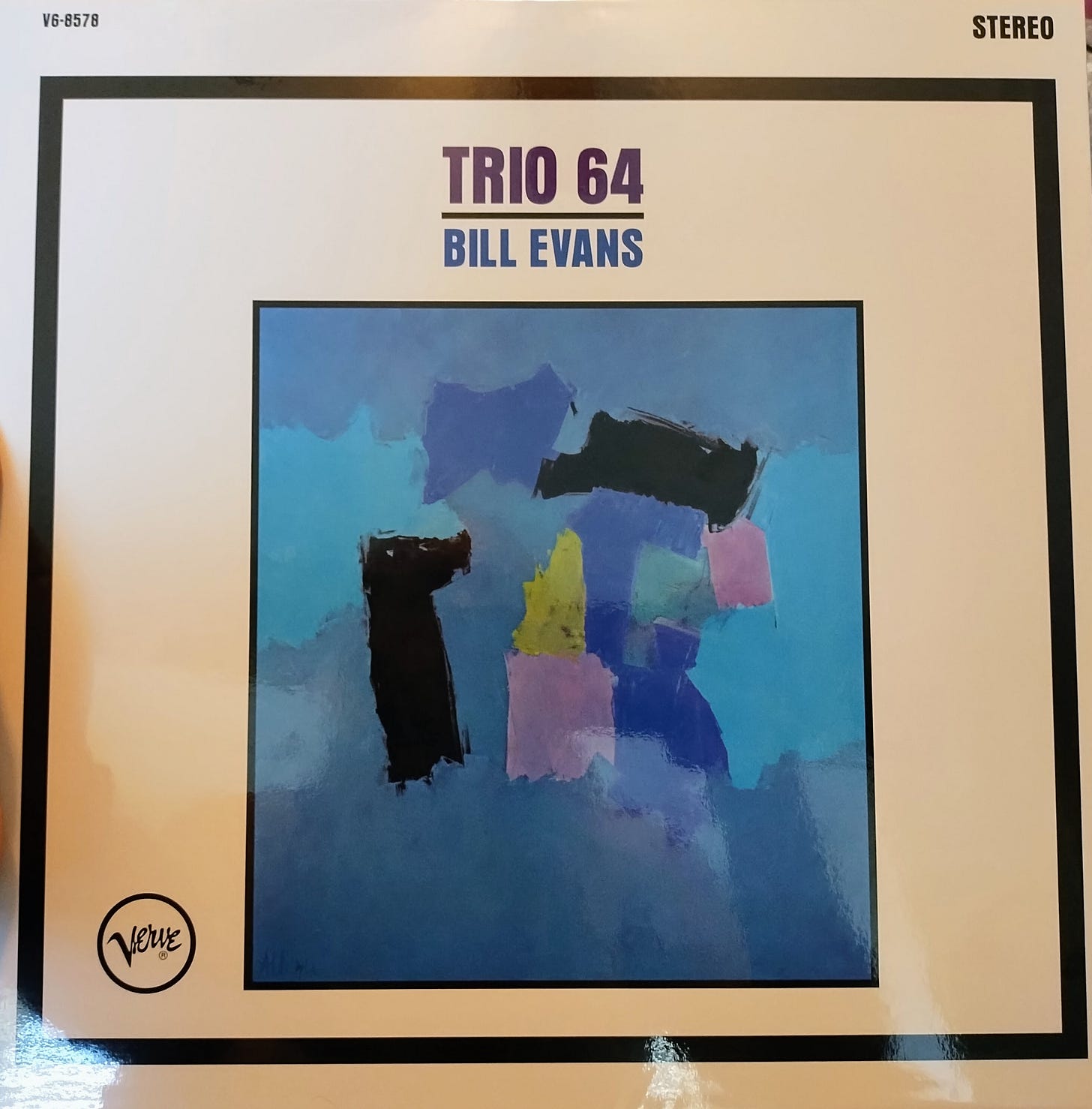

Trio 64

The first thing I noticed upon hearing the start of the first track on side A, of Bill Evans’s album Trio 64 (a stereo recording), is the expansive soundstage on my home audio system, with acoustic bass way off to the left, seeming to originate to the left of the left tower speaker; and the drums to the right seeming to be located to the right of the right tower speaker. I don’t go into the technical details of my stereo set-up, but I will say it has been a labor of love and soldering iron-burned fingers to put together.

Evans’s piano is right-center, a bit behind the line connecting the speakers speakers. Paul Motian’s drums are, as I said, to the right, and Gary Peacock’s bass is off to the left. This is a super-trio, composed of some of the jazz greats of the latter half of the 20th century. The LP is an “audiophile,” 180-gram, Acoustic Sounds series (Verve label) reissue. The subtle aspects of Peacock’s bass—its delicious, “rosiny” stickiness, its lightness and brightness, and his muttering to himself in tune with his playing, a sort of scat-singing reminiscent of many jazz pianists’ mutterings—come through wonderfully. There is not much emphasis on the low end, but it’s there. The piano of Evans is clean as can be, and this is a contrast with the similar reissue, Evans’s Trio ‘65, which has a distorted and muddy piano (I commented on this in my review of the Schiit Audio Valhalla 2 SET OTL tube headphone amp and preamp, here: https://open.substack.com/pub/hanscox/p/review-schiit-audios-all-tube-valhalla — but see below).

Paul Motian is a drummer I have heard before, and I have not taken much notice of his playing, which I am sure is excellent. On this album, in an intimate trio format with Bill Evans leading the way, his drums stand out as a full third of the trio; he is not just background but is equal, in the mix, with Peacock and Evans. The fidelity of the recording is outstanding, allowing the listener (here, me) to hear subtleties in his cymbal work that might be lost in a lesser production. There is a way of playing a cymbal that sounds to me as if the drummer has sent it spinning, and Motian does just that, here. He features his kick drum only sparsely and to good effect, and it has a strong knocking as if a muffled hearing of someone knocking on a heavy wooden door.

Evans’s piano may be single-miked here, since it seems to come from one place, while many later recordings of jazz pianists feature at least two microphones, which tends to spread the keyboard across the soundstage. I think I am getting a less-live impression from Evans’s piano than I am from Peacock’s bass and Motian’s drums. Evans’s piano seems situated behind and between the bass and drums, perhaps making his playing seem even gentler than it is in person. The second side features more of the low end of Peacock’s bass. Motian sticks mostly to using brushes on his cymbals throughout, punctuating mostly with the occasional knock of his kick drum.

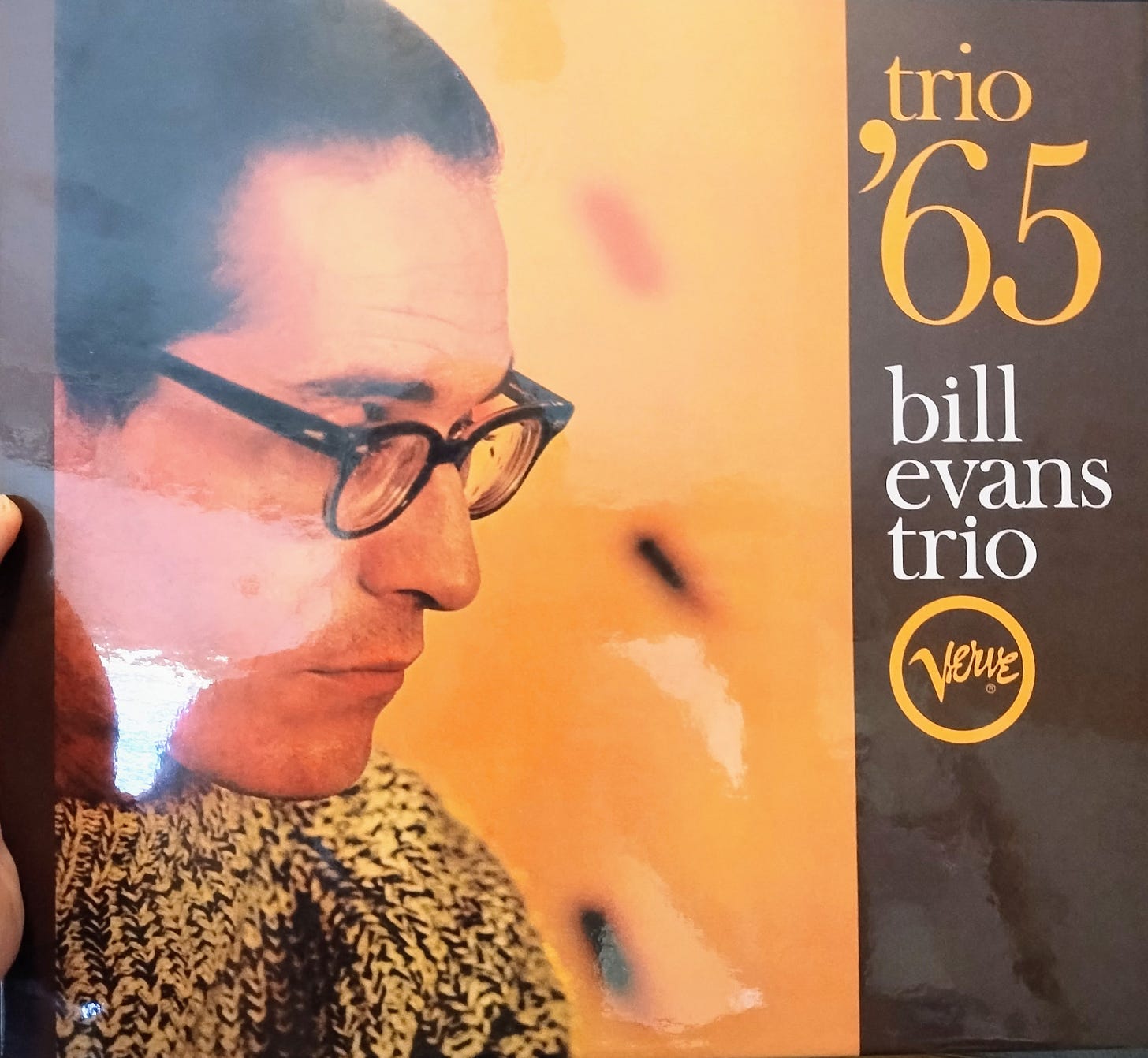

Trio ‘65

I have to say, Evans’s piano sounds much better through the speakers than I remember it sounding through headphones, through the headphone amp output. Still, chords come through unclearly, with separate notes being mushed together a little. I think Evans’s piano is single-miked on this album as well, and its placement on the soundstage is identical to that of Trio 64, which is right of center. Single-note lines, of which there are many, sound clearer. Chuck Israels’ bass is to the left, and it seems to come from the left of the left tower speaker. His bass tone is not “rosiny” or “sticky,” as I said Gary Peacock’s was. There is some treble to it, but mostly it has an emphasis on the lower end, and each note sounds more percussive than pizzicato.

Evans’s piano is more forward in the mix than Israels’ bass is but is not as forward as Larry Bunker’s drums. Bunker’s drums are located to the right of Evans’s piano. In contrast with Paul Motian’s style on Trio 64, Bunker relies heavily on the snare, and he uses sticks and brushes. He opens himself up on a bouncy track, “Our Love Is Here to Stay,” combining a steady classic jazz rhythm on the ride cymbal and performing some splendid tricks with the other hand, on the snare. Bunker’s playing is much snappier than Motian’s was. Overall, Trio ’65 is more up-tempo than Trio 64. Further listening, now on side B, proves out that Israels’ bass is the least prominent instrument in the mix. Like the bassist Richard Davis, Israels plays in the background, not standing out the way Ron Carter or Alex Blake(!) tend to do.

On “Come Rain or Come Shine,” Israels takes a solo, accompanied by Evans and Bunker. Even so, it’s more like an elaborate bass accompaniment, most of it, than it is like a bass solo. And there are no acrobatics in it. Israels’ playing helps to mellow out the album, which has more exciting piano and drums than Trio 64 does. On Trio 64, Gary Peacock’s brighter and more adventurous playing tended to add a little bit of an upbeat feel to an otherwise slow and gentle album.

†

Just as the bassists complemented—through contrast—the piano and drums, I think the albums Trio 64 and Trio ’65 complement each other. The amount of music an artist performs is much greater, typically, than the amount that is committed to a high-quality record. Imagine if every Bill Evans or John Coltrane, or Sun Ra performance had been recorded with high production value. The impressions that people, like me, who are too young to have witnessed their performances, would likely be different and better informed than is possible given the comparatively meager sum of performances that exist as albums.

Thanks for the recommendations!