When I heard Underworld’s “Cowgirl,” I was seeing beyond the bounds of the death metal and hair band and grunge sounds I was then steeping in. It was a dark night on a rural road, and I think my friend was trying to pick me up, and I was that obtuse—I wasn’t sure if she just wanted to stop and listen to some music! And I was skittish. But the opening synthesizer and vocal samples were like nothing I had ever imagined. “Cowgirl,” along with Nirvana’s “Territorial Pissings,” remains one of my five favorite tracks.

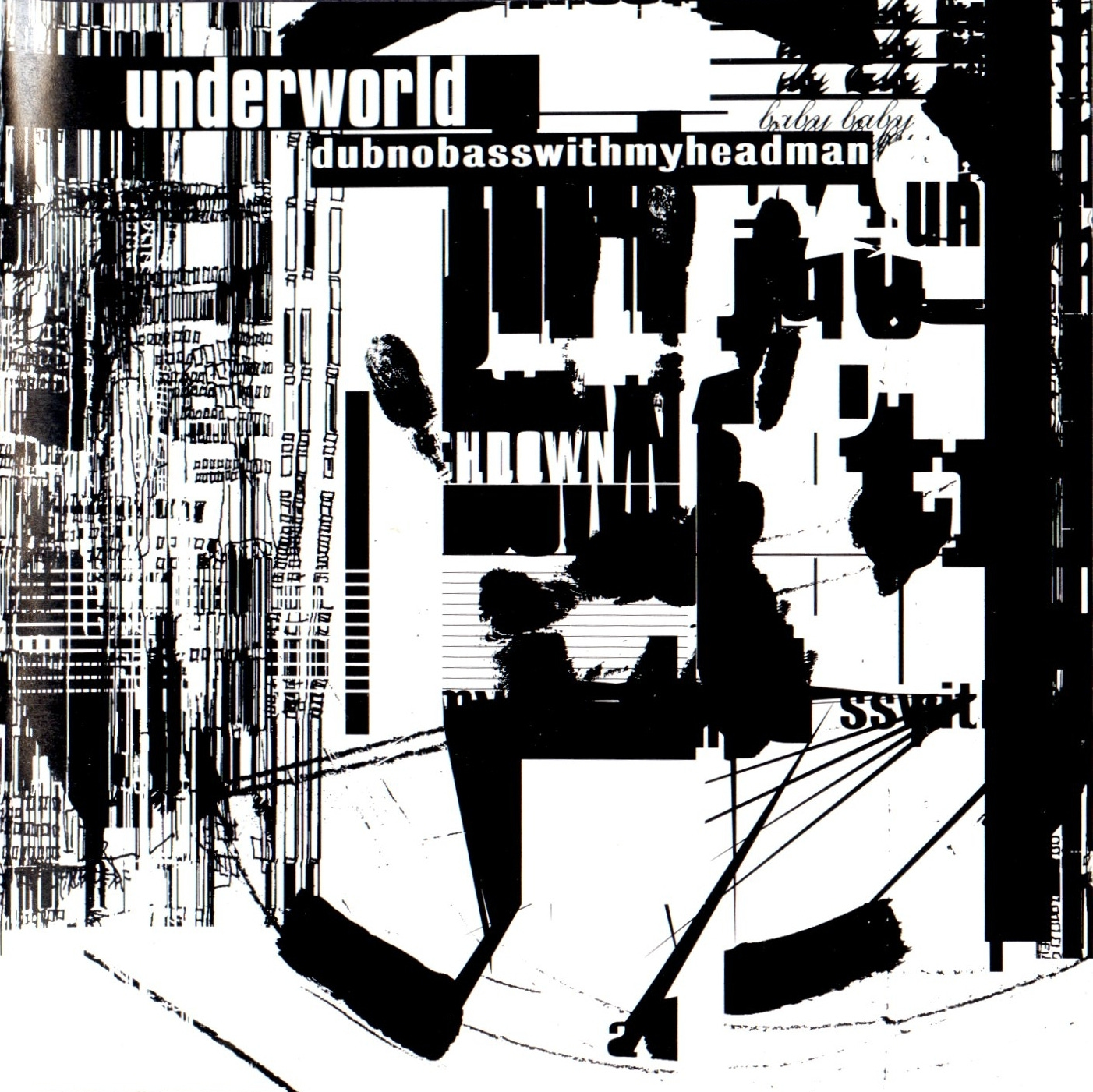

The rhythm figures in the track repeat again and again, often changing from one timbre/synth to another. (This combination of repetition in rhythm and melody, while there is variation in timbre, reminds me of Caterina Barbieri’s track, “Gravity that Binds.”) The pounding four-on-the-floor bass drum gets my body moving, and the accents get my head tossing. The visuals in my mind are steered (no pun intended) by the distinctive graphic on the cover, shown above: black-and-white collage done by an artistic collective, featuring Underworld members Karl Hyde and Rick Smith, called Tomato. I only just learned that Tomato was not a single person. The things I sometimes take for granted, as already known!

Qobuz link: https://open.qobuz.com/album/0060253792928

Tidal link: https://tidal.com/browse/album/77652965?u

Our dad had a then-late-model Nissan Maxima, which had not only a moonroof, but it also had a Bose-brand stereo system. Its bass response allowed me to hear bass I had never heard in my music. The bass synth pulsing into view, on track one of dubnobasswithmyheadman, “Dark Train,” catches the ear, and a four-on-the-floor bass beat, prominent throughout the album, breaks in. This is a dance album. The various synth sounds and vocal samples add a strange atmosphere to “Dark Train,” and to the whole album. The words are poetry.

“Mmm…Skyscraper, I love You,” track two, has a drum sound I’m not fond of. But on good stereo equipment, it does not have the overly heavy mid-range sound that hurts my ears. When I think of this album, I think of hearing it on my old black-plastic-crap (or BPC; see Robert Harley’s excellent book on music audio, The Complete Guide to Hi-End Audio) Sanyo-brand CD-tape-radio boombox with “bass boost” button. Certainly, that colors the sound in my memory, and not for the better. My wonderful IEMs are pumping out the smooth, deep bass right now, and the “porn dogs” are “sniffin’ the wind for somethin’ new,” as Karl Hyde puts it in “Skyscraper.”

“Surfboy,” is, for me, like rich milk chocolate. Its huge bass drum sound and strange sonar-ping-like beeping, along with a rapid one-two on some sort of (steel?) drum, combine with male and female vocal samples, such as a female voice that says “talk to me / talk to my machine,” to create a feral-spirited dance track that always gets my head rocking.

This is an album I haven’t heard anywhere except when my high-school friend or I have played it. I voted for “Cowgirl” to be song of the year when I was a senior in high school, and I’m sure I was the only one to do that; it was long after the song had been released, and I didn’t know anyone who listened to the music. One thing about dubnobasswithmyheadman, is that I enter into an aureal place and accept its rules and practices as given. I don’t question what’s going on, I only love what’s going on. As with a lot of poetry, I think it best just to accept what I’m being told—not as some historical commentary on actual fact, but as a transcendant view of something beyond mere description and denotation. The omniscient narrator is appropriate for some listening, to hear the world being created in the music. On a second consideration, this narration can always be questioned, but one should, as when reading anything, come to a sense of what the claims are or what is supposed to be happening, before formulating any counter-argument or other interpretation. Even in the case of the “death of the author,” we then have an artifact which we have no reason to question at first blush. An ancient coin may be an ancient counterfeit coin, but it would still be ancient and an artifact. I think what I’m trying to get at is, I try to give the music all authority on the first few hearings. As with a lot of Nietzsche’s writing, I find that what I’m being told is to imagine a what-if, a world or interpretation of the words, that would make the words true.

Take “Spoonman,” for example. I remember thinking it sounded weird. Right now, I’ve been let into the place from which it comes, and I love it. I am “released” toward it, letting it be, saying both yes and no to it, and not exerting any will toward what I might wish it were instead of what it is; my relation to it is beyond the distinction of willing and unwilling—as Heidegger’s “Guide” said, in the first of the “Country Path Conversations,” “I only will non-willing.” My relation to the music is nothing having to do with the realm of the will or of willing, and it is not passivity, either, which still remains within the realm of the will. The track is manifesting itself as what I allow it to be.

“Tongue” is a guitar and vocal themed interlude, which is, for me, a pause before “Dirty Epic,” a poem of many seemingly disconnected scenes and images, with deep bass and more four-on-the-floor drumming. There is a descending synth that is so low, I couldn’t hear it clearly until I played it on the Maxima’s stereo. The primary aspect I see in Karl Hyde’s vocals is that they succeed in creating compelling, arresting images. There are at least two vocal threads in “Dirty Epic,” one of which is a distorted sound as if we’re hearing, unclearly, one side of a telephone conversation. Hyde sings on this track, as he doesn’t on any other track. There is melody here; this is bigger than a poetic recitation.

Underworld's 1994 album is like an old trinket I keep taking out of my pocket or bureau drawer, and re-examining in fond remembrance and ever new discovery of it being what it is at that moment. It is like something that belonged to a deceased relative. Even when I first got the album, dubnobasswithmyheadman seemed to be from a world in which I played no part. Even now, I feel disconnected from the music, as if it does not belong to me but still belongs to someone who is no longer present to hold it. And I cherish it and dance to its rhythms.